Use the App on UVA grounds

Visit the augmented sites indicated on the UVA Reveal Map. Once at a site, click the “Reveal” button and point your device’s camera at the augmented object. The augmentations should appear on your device.

Use the App on UVA Reveal website

Open the app click the “Reveal” button and point your device’s camera at the trigger image to the left. The augmentations should appear on your device.

History of the Mural

Lincoln Perry composed the mural known as “The Student’s Progress” over the course of 16 years. The mural has 29 panels and follows the life of the fictional UVA student, Shannon, from her undergraduate days and into her adult life as a professor at the University.

“The Student’s Progress” was composed in two primary stages. Perry began painting the mural in 1996 and the first stage of 11 panels was completed in 2000. The panels that constitute this first stage depict Shannon’s time as an undergraduate music major at UVA. While the mural was officially “complete” at this time, Perry states that he was “drawn to the idea” of continuing Shannon’s story, and in 2006, he petitioned UVA President John T. Casteen III to continue working on the mural, a petition which was granted. The second stage of the mural was thus completed in 2012, and it shows Shannon’s marriage, her return to UVA as a professor, and her daughter’s own journey within the university.

Perry’s Artistic Process

While the first 11 panels were painted off-site and later installed in Old Cabell, Perry painted the latter panels directly onto canvases that he had mounted on the walls in Old Cabell. His process involved creating initial maquettes, or sketches that were to scale, then outlining the figures and architectural shapes in charcoal on the walls, and finally painting over the charcoal using a technique that Perry calls “optical mixing,” which involves layering several colors while nonetheless allowing the bottom layers to show through at various points. Additionally, Perry used as many real models as possible throughout his artistic process. He states: “Having a model sit can give an extra level of specificity and surprise, an energy sometimes lost when working from one’s head or from drawings. I never work from photographs if I can help it.” In fact, some of the individuals depicted in the mural are identifiable professors and figures at the University, including former UVA President John T. Casteen III, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and English professor Charles Wright, English professors Jerome McGann and Lisa Spaar, architectural history professor Richard Guy Wilson, art history professors David Summers and Paul Barolsky, and studio art professor Richard Crozier, among others.

Subject Matter

Perry intentionally depicted events that reveal the manifold difficulties of being an undergrad at the university. In fact, he stated that his very choice to show the life of a woman in the university was purposeful. Perry claimed: “I wanted someone who was not breezing through life, and it seems to me that women have more of an uphill battle than men. I wanted her to be having a hard time. Life is hard, and certainly school is hard.” Events that Shannon faces include physical trials (such as dropping her violin and twisting her ankle) as well as emotional trials (including various relationships, Shannon’s marriage and pregnancy). Of these trials, Perry has stated: “The idea is that somehow or other [Shannon is] not waltzing down the Lawn in majesty. She’s fighting.”

Controversy Surrounding the Mural

After the gang rape allegations broke in Rolling Stone on Nov. 19, 2014, UVA professors and advocacy groups on grounds drew attention to certain disturbing images depicted in Perry’s mural, including the image of a professor having an affair with a student. In her article “The UVA Gang Rape Allegations Are Awful, Horrifying, and Not Shocking at All,” UVA Associate Professor of Music, Bonnie Gordon, wrote: “A very expensive mural called ‘The Student’s Progress’ covers the entire foyer and stairwell of Old Cabell Hall, which is also the University’s premier auditorium and the favored space for visiting dignitaries. The mural depicts, among other scenes of daily life at the University of Virginia, a male faculty member standing on a porch and tossing a mostly naked student her bra as his beleaguered wife comes up the stairs. My students and I have pointed out that wildly inappropriate section of the mural to faculty, administrators, students, parents, and donors, but so far, no one has been particularly horrified. The mural is proudly displayed and is prominently featured on UVA tours.” Since Gordon’s article, there have been numerous protests against Perry’s mural, and several students have called for the mural to be removed. The University continues to debate this issue.

Women at UVA

“A plan of female education has never been a subject of systematic contemplation with me.” –Thomas Jefferson

The particular representation of women in the mural should be discussed in the context of the history of women at UVA as a whole. Women have always inhabited the University of Virginia: as wives, as mothers, as slaves. But it wasn’t until the 1880s that women began attending the school as students, and UVA did not become fully coeducational until 1973. Women have fought for entrance into Jefferson’s school repeatedly over the university’s long history.

Women began enrolling at UVA for this first time in the summer of 1880. That year, the University became the host to Virginia’s first Normal School for teacher training. Teaching was one of the few professions open to women in the 1800s, and as such, over half of the attendees of the 1880 normal school were women.

In 1892, Caroline Preston Davis petitioned for permission to take the school’s graduating examinations in a field typically dominated by men: mathematics. Caroline Davis’s work was such high quality that she was awarded distinction. Nonetheless, UVA would not grant her a degree. She was given a certificate of proficiency instead. Davis was the first of a small group of white women who were allowed to attend UVA as “special students” in the 1890s. During this time, women were not allowed to take classes with men, but they were allowed to be tutored individually and to take university exams. This small window of opportunity was brief, however, as the Board of Visitors voted to prohibit any woman from enrolling in these programs in the future just two years later, in 1894.

Women’s colleges and coeducational opportunities were growing in America by the 1900s. By 1900, 71% of US colleges and universities were coeducational to some degree. Yet, at the turn of the twentieth-century,there were no still four-year colleges for women in the state of Virginia. This led Mary Mumford of Richmond to spearhead an effort in 1910 to establish a coordinate college for women at the University of Virginia. Coordination would have allowed women to have access to their own, women-only classes at a sister college in Charlottesville while still utilizing the library, laboratories, and teaching staff at UVA. Even this was too much for the elite men of the legislature and UVA. The proposal to establish a coordinate college at UVA was voted down every year from 1910 to 1920.

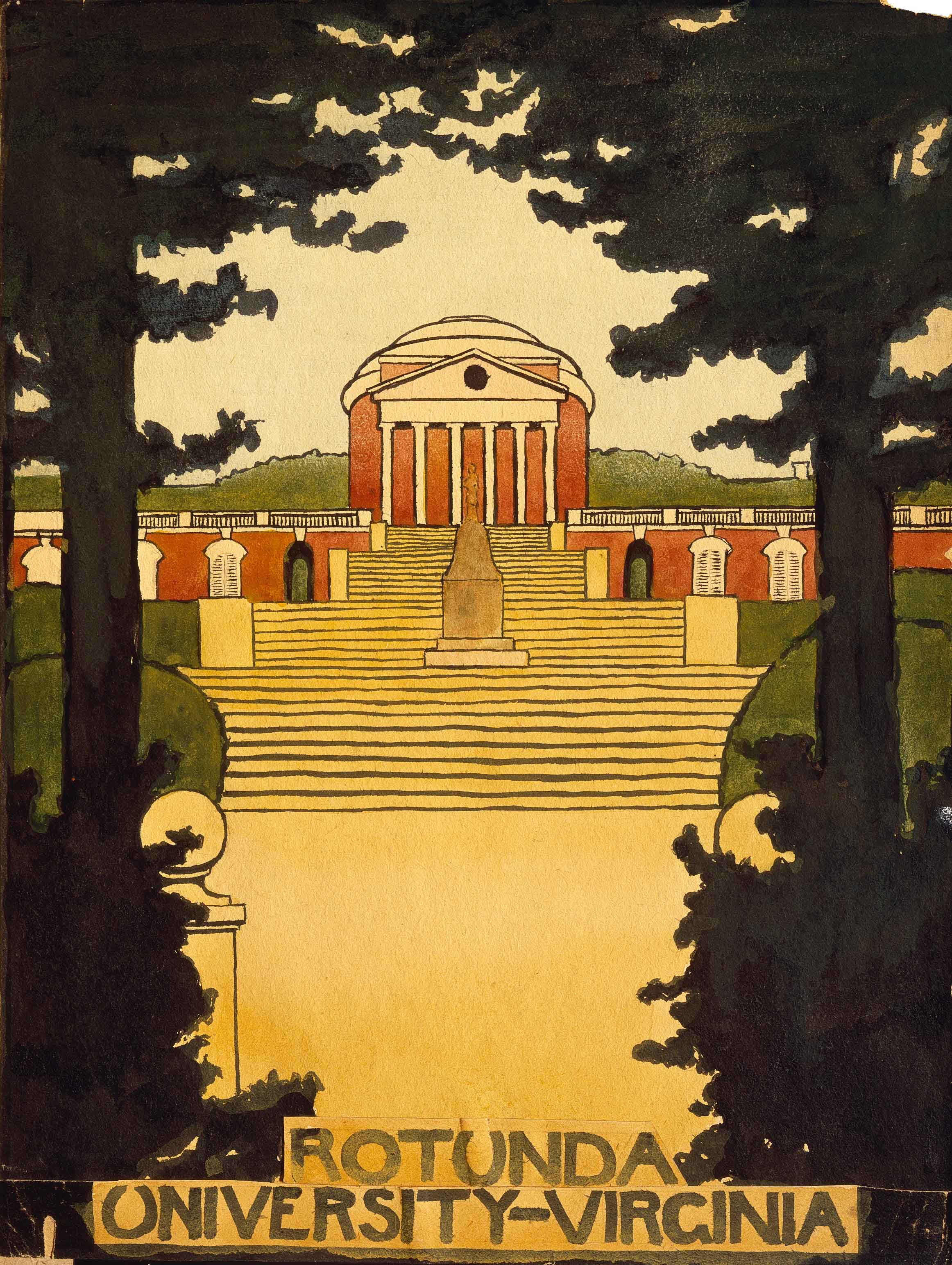

However, the university did remain open to women in special summer courses. Among the women learning and teaching at UVA in the 1910s was famous artist Georgia O’Keeffe. O’Keeffe enrolled in drawing classes at the University of Virginia in 1912. The very next year, O’Keeffe was teaching her own class at the school. See O’Keeffe’s early paintings of the Rotunda, below:

In 1920, the University of Virginia opened its graduate and professional program to select women. The first female law school graduate was Elizabeth Tompkins, who graduated in 1923. However, when Alice Carlotta Jackson tried to take advantage of this new opportunity in 1935, Alice was denied not because of her gender, but because of her race. Alice was the first known African-American to apply to a graduate school in Virginia. Alice grew up in Richmond, Virginia, and received her BA in English from Virginia Union University. She attempted to enroll in UVA’s French Master’s Program. The UVA Board of Visitors denied her entrance based on the Jim Crow laws and “other good and sufficient reasons.” Barred from higher education in her home state, Jackson earned her M.A. from Columbia University in New York City. Jackson went on to spend a lifetime teaching and advocating for civil rights. After her passing in 2001, Jackson’s family donated her personal papers to the Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia.

The UVA Board of Visitors finally voted to allow women entrance into all programs in 1969 with plan to admit female students gradually. In 1969, UVA would accept qualified wives and daughters of male students and staff members at UVA. The University would then gradually increase their numbers, capping female enrollment at 35% of the student body by 1980.

This halting pace was not enough for the four women who sued to gain entrance to the university in the spring of 1969. Virginia Scott, Nancy Jaffe, Nancy Anderson, and Jo Anne Kirstein filed a complaint arguing that UVA “severely discriminates against women in their admissions policies.” John Lowe, a recent UVA law school alum and American Civil Liberties Union lawyer, represented the four women. The court ultimately agreed with these women, and it ordered UVA to become fully coeducational within three years.

Once women gained admittance to the University, they worked to improve their conditions on Grounds, fighting for equal access to residential facilities, bathrooms, student groups, and sports programs. In 1972, Cynthia Goodrich became the first female resident of the Lawn. In 1989, University of Virginia students began to organize Take Back the Night marches to protest sexual assault on campus. A consortium of UVA organizations continue to host Take Back the Night events every April. These students help lead the effort to protect and empower victims of sexual assault and domestic violence, no matter what their gender or sexual orientation.

Bibliography

- Ann Beattie and Lincoln Perry, “Interview: Lincoln Perry by Ann Beattie,” BOMB. Oct. 1, 2005.

- Sierra Bellows, Carianne King, Emma Rathbone, "Women at the University of Virginia," University of Virginia Magazine. Spring 2011.

- Savannah Borders, “Old Cabell Hall Mural Proves Controversial: One Profession Describes Mural as ‘Red Dot,’” The Cavalier Daily. April 4, 2016.

- Nora Caplan-Bricker, “Can a ‘Teaching Moment’ Over a Sexist Artwork Really Combat Rape Culture at UVA?” Slate. April 26, 2016.

- Kimberly Diana Jacobs, "Quotas and the Status Quo: Women at UVA," (Re)Imagining Women in STEM..

- Jane Ford, “Old Cabell Hall Mural Expands to Encompass a Lifetime of Learning,” UVA Today. Nov. 27, 2012.

- Bonnie Gordon, “The UVA Gang Rape Allegations Are Awful, Horrifying,and Not Shocking at All,” Slate. Nov. 25, 2014.

- Peter Jacobs, “A Prominent Mural on UVA’s Campus Appears to Depict a Professor’s Affair with a Student,” Business Insider. Nov. 26, 2014.

- Jane Kelly, “John Lowe ’67: A Hero of Coeducation at UVA,” University of Virginia School of Law. Sept. 29, 2017.

- Amy McCandless, “Maintaining the Spirit and Tone of Robust Manliness: The Battle against Coeducation at Southern Colleges and Universities, 1890-1940,” NWSA Journal. University of Johns Hopkins Press. Spring 1990.

- Larissa Mehmet, "Breaking and Making Tradition: Women at the University of Virginia," University of Virginia Special Collections Exhibit. 2003.

- Priya N. Parker, "Alice Carlotta Jackson: First African American to Apply to U. Va. (1935)."

- Priya N. Parker, "Virginia Anne Scott: Challenges the University's Admission Policy on Coeducation (1969)."

- Rob Shimshock, “UVA Forms Committee to Address ‘Problematic’ ‘Party Culture’ Mural,” Campus Reform. April 6, 2016.

- Special Collections Staff, "A Guide to the Papers of Alice Jackson Stuart, 1913-2001," Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. 2003. Web..

- Katherine Smith, “SMITH: Remove the Mural in Old Cabell: ‘The Students’ Progress’ Reflects Poorly on U.Va.’s Values,” The Cavalier Daily. Oct. 16, 2017.

- Courteney Stuart, “Old Cabell Hall Mural Controversy,”

- Take Back the Archive.

- “The Murals of Lincoln Perry,” Parts 1-3. Video series on Youtube

- “The Mural at the University of Virginia”