Use the App on UVA grounds

Visit the augmented sites indicated on the UVA Reveal Map. Once at a site, click the “Reveal” button and point your device’s camera at the augmented object. The augmentations should appear on your device.

Use the App on UVA Reveal website

Open the app click the “Reveal” button and point your device’s camera at the trigger image to the left. The augmentations should appear on your device.

About the augmentation of the French Department

This project is designed for both UVA students and visitors to the French Department. The materials selected for the augmentation are in French, which allows the application to turn into a pedagogical tool in the future. This fact, however, should not limit the experience to only those familiar with the language or interested in learning it. On the contrary, those unfamiliar with French language and culture should not miss the opportunity to explore an unknown territory. Chances are they will benefit from it equally, if not more. The sounds, images, and narratives presented in this project are specifically curated to evade immediate interpretation, whether one speaks French or not.

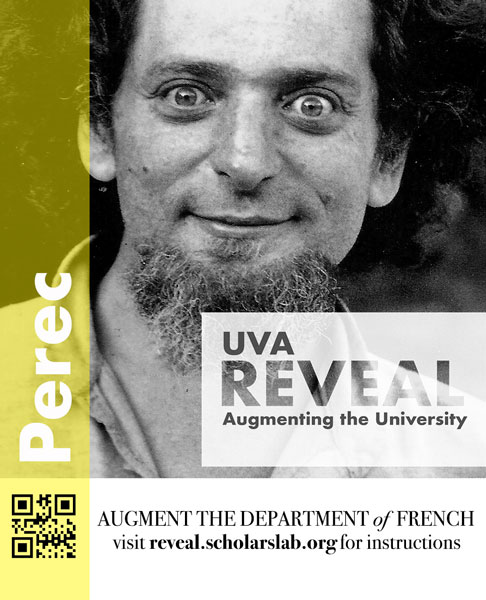

The goal of this project is to engage the viewer’s imagination and allow it space to deploy freely without restrictions. The artists presented here –François Rabelais, Luc Ferrari, and Georges Perec– are in constant dialogue with the world around them and aware of the forces shaping it. All three took interesting creative liberties by transgressing boundaries and inventing their own artistic processes. Through language, musical composition, or the mere act of observing and recording the quotidian, the selected works share a common thread: to explore and to reveal reality.

Rabelais, a sixteenth century physician, monk, and fiction writer, allows us to reflect on augmented reality outside of the current, heavily technical, aspect of affairs. As it turns out, ambient literature1 is not a recent invention but only enabled by recent advancements in technology. Following Rabelais’ intuition of the world being a recording device, albeit without the playback button, 20th century composer Luc Ferrari set out to make available to the ear some of the world’s scattered acoustic archives. As for Georges Perec, member of Oulipo (workshop of potential literature) and author of Life a User’s Manual, made everyday minute observations one of his most powerful creative processes, artfully lifting the weight of creative writing.

As we will see, when recorded and played back, reality reveals itself piecemeal. Fragment upon fragment, there is always something more to add, but we should be wary of expecting a total sum.

Augmenting the Fragmented Reality

As the early 20th-century philosopher Walter Benjamin argued2, a fragmented world can be seen as both a dangerous place, leading to barbarism, and as an opportunity to collect and re-assemble those fragments in an endless creative intervention. Benjamin discovered there is often something missing when we experience the world around us, whether due to displacement or the passage of time. He called this contextual dimension “aura.” If things seem out of time and place, how can we salvage their historical context or recover their aura?

Augmented Reality offers new ways of connecting a fragmented world. By augmenting the French Department, UVA Reveal hopes to thicken the colloquially thin air by superimposing layers of content (excerpts of books, sound, and video clips) between the viewers’ perceptive organs and the physical realm. This in-between space should not be mistaken as empty, though. It is the space where mental faculties and affects operate, enabling the viewer to connect with the world. The issue, then, is how not to interfere too much with this vital, internal, as much as external, space? How to make sure not to block but to incite imagination, to make available a variety of possibilities instead of projecting one’s own ideas and views? One answer to these questions may be found in the technology itself, since it is a technique of a palimpsestic rendering of reality.

By pulling three, seemingly random, French artists, spanning a period from Renaissance to post-modernity, and blending their work with the physical space of the French Department at UVA, we hope to offer a glimpse of France’s rich cultural background, albeit presented through our personal lens and research interests. The project, however, should not end with this contribution. We extend the invitation to our colleagues in the French Department and in all other departments at UVA to collaborate, keep adding materials, and build more augmented sites. In so doing, we will continually ignite the curiosity and desire of future students for further exploration in the stacks, in a course offering, or directly in France, the Francophone world, and beyond.

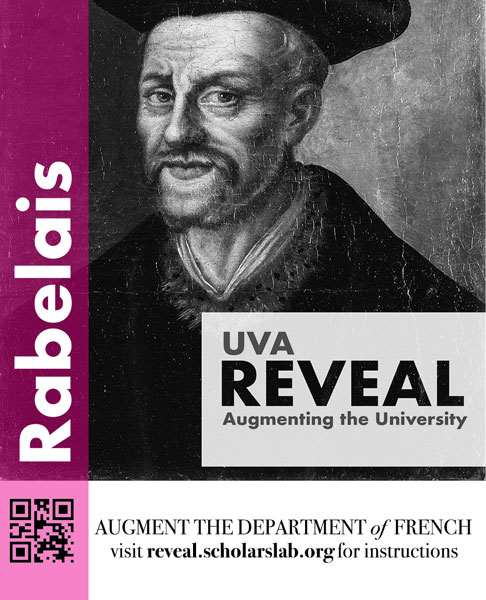

1. Rabelais

UVa’s Special Collections Department is the repository for one of the most important American collections of rare French books: The Douglas H. Gordon’s Collection. An earlier digitization project made many of the Douglas H. Gordon Collection treasures widely available. Among the Renaissance rarities in the collection are two unique editions of François Rabelais’ Le Quart Livre3.

Rabelais, creator of the giants Gargantua and Pantagruel, in his Fourth Book (Le Quart Livre) sets his protagonists off on a voyage across the ocean. During their adventures at the confines of the Frozen Sea, Pantagruel and his crew are hit by “a storm” of strange voices and noises.

“[W]ords and cries of men and women, the hacking, slashing, and hewing of battle-axes, the shocking, knocking, and jolting of armours and harnesses, the neighing of horses, and all other martial din and noise, froze in the air; and now, the rigour of the winter being over, by the succeeding serenity and warmth of the weather they melt and are heard.” (The Fourth Book, Chapter LVI)

This episode, known as the “Paroles Gelées” (Frozen Words), sets the tone for the augmentation of the French Department as it offers an entry point to reflect on Augmented Reality, albeit anachronistically. Indeed, digitally reproduced artifacts, combined with location-based metadata, and displayed in physical spaces through Augmented Reality techniques, make us aware that places are not devoid of content. The world is a huge recording device for all sorts of major historical events, or infra-ordinary mundane events, inscribed in its tissue.

Strangely enough, Rabelais’ episode of Frozen Words resonates with Charles Babbage’s hypothesis of the world being “one vast library.” British luminary scientist of the Victorian era and one –of the many– fathers of the computer, Babbage set out from the principle of the “equality between action and reaction” to demonstrate that “[n]o motion impressed by natural causes, or by human agency, is ever obliterated.”4

Whether we accept Charles Babbage’s claim or not, the technological milieu we are living in is saturated with recording devices, sensors and smart objects, constantly storing information in the cloud. Babbage’s intuition then strikes home:

“[W]hat a strange chaos is this wide atmosphere we breathe! Every atom, impressed with good and with ill, retains at once the motions which philosophers and sages have imparted to it, mixed and combined in ten thousand ways with all that is worthless and base. The air itself is one vast library, on whose pages are for ever written all that man has ever said or woman whispered.”

Now, if the prospect of listening to “whole handfuls of frozen words” in a unknown language frightens you, as it did Panurge, don’t hasten away and make all the sail you can just yet. Rather, “consider a little,” following Pantagruel’s equanimity. Words, when melted in a semantically disintegrated soup still retain their quality as sounds. Listen to “some large ones go off like drums and fifes, and others like clarions and trumpets.”

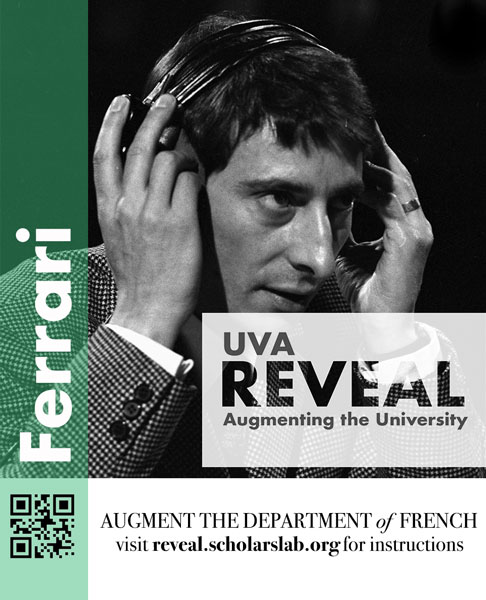

2. Luc Ferrari

Rabelais’ comparison of words to the sounds of musical instruments challenges us to a fresh relationship with language, and it works as an appropriate segue to the next installment of the French Department augmentation project. Here, we will continue our journey through spoken words and sounds with Luc Ferrari, a contemporary French composer and avid reader of Rabelais.

Drawn to everyday sounds, Luc Ferrari found such sounds enticing and welcomed them in his music, including words plucked from their original context and reassembled into new musical phrases. To compose, then, was less an isolated soul-searching activity than letting the world speak for itself.

An ear attuned to the world, as Rabelais has shown, doesn’t always find meaning. To make meaning, one may need elements that are not immediately available, such as context or a foreign tongue. Nevertheless, the acoustic experience remains, collecting all sorts of sounds and voices in its passage, without a particular attachment to semantics. That’s Ferrari’s approach to composition. Voices for Ferrari have their own semantics, often obscured by the words they utter. The problem with words is that they beg for interpretation and that’s the condition (disease) of Western civilization –a civilization of priests, as Roland Barthes put it.

“Presque Rien” (Almost Nothing), “Promenades Musicales” (Musical Walks), and “Anecdotiques” (Anecdotals), three subdivisions of Ferrari’s ambient musical idiom, are all ripe with short linguistic spasms which encourage contemplation rather than interpretation.

After this brief interlude, Chantal, ou le portrait d’une villageoise5 (Chantal, or the portrait of a village woman) is the main highlight of Luc Ferrari’s augmentation.

The piece was recorded by Luc and Brunhild Ferrari in the summer of 1976, but not released until 2009. While vacationing in the small village of Tuchan in Corbières, Luc and his wife Brunhild met and interviewed many of the village’s “libre penseurs” (free thinkers), among them Chantal, a fierce young woman with a disarming sense of honesty and charm. Probed by Luc’s and Brunhild’s questions, Chantal opened up about her hardships, views on politics, isolation in a remote village in the South of France, and her search for emancipation. Their conversation would become legendary.

In the context of this project, Chantal’s portrait adds to the female voices we have chosen to amplify, and offers a different perspective to Lincoln Perry’s female character, Shannon, depicted on the mural of Old Cabell Hall.

Unlike Shannon’s fictionalized and rather muted but successful progress in life, Chantal speaks for herself, albeit disillusioned concerning the power of words to convey a complete portrait of her. “Tu me demandes des mots, c’est tout. C’est pas tellement les mots qui comptent dans la vie. Les mots c’est facile, c’est tout.” (You ask me for words, that’s all. Words are not the only things that count in life. Words are easy, that’s all.)

The following clips are taken from the original recording, and are presented with a little note in English for non-Francophone speakers. A shorter version of the clips are also available in the UVA Reveal app.

By now, the interview is almost over. For the remaining ten minutes the microphone runs almost without anyone really noticing it. Brunhild and Chantal have a more relaxed, in-depth conversation about love, being in a relationship, and friendship. “Do you have a friend to talk about these things?” she says. “There are things I can’t even admit to myself,” Chantal answers.

Chantal, today in her sixties, still lives in Tuchan. She works at a local wine company and is actively involved in politics as member of the city council. She has married twice since Alain, with men she cared more about. Today, she lives with her third husband. For about fifteen years,since their sex life went from scarce to non-existent, she has been seeing another man. “J’aime ma liberté sexuelle,” said to Carole Rieussec in an interview in 2014, “you can make a note of that.”

3. Georges Perec

To close this augmented reality experiment in the French Department, we chose another experimental work in alignment with Luc Ferrari’s approach of recording the the world as it is. “I am not always involved with narrative. […] I am interested to see what happens when time passes,” Ferrari said in an interview with John Palmer in 1999.

Georges Perec’s work An Attempt At Exhausting A Place In Paris6 is itself a record of “what happens when nothing happens.” It consists of an attentional exercise: observe and make a note of everything that happens within the field of vision. Georges Perec carried out the experiment over three days at the place Saint-Sulpice in Paris. The approximately 50 printed pages that resulted read like a log, or a police report, only there is no crime –other than killing time.

In what seems to be the invention of a method, one that many writers after him have adopted and expanded upon, Perec’s writing is a slow, meditative practice of observation in an attempt to completely blend in with a given locale at a given moment. In a programmatic note “Apprendre à bredouiller”7 (Learn to stutter), Perec wrote: “essayer d’être modeste, plus que modeste : nul. évident.” (sic) (Try to be modest, more than modest, null, obvious.) Lifting the weight of a poetic, heavily figurative language –metaphor literally means transport– dismissing the search for a thrill, whether in a different place or a different time, past or future, Perec suggests a “return” or an “awakening” to the present. Competing with an array of modern day recording apparatuses (tape recorder, camera, etc.) that easily bring the banality of the present into focus, Perec’s writing also had to suppress a striving for the sublime and reconnection with record keeping –writing’s archaic purpose.

Since its publication 1975, An Attempt At Exhausting A Place In Paris has been adapted in many different formats8. The following excerpts are from Jean-Christian Riff’s movie of the same title. Riff films Saint-Sulpice, in 2007 –thirty years after Perec’s experiment– with the same premise: record “everything that happens when nothing happens.” His understated flow of images of everyday contemporary Paris are mixed with a voice-over reading of Perec’s original text. Consequently, Saint-Sulpice Square becomes a stage for tracing the scenes and micro-events, the trigger for Perec’s writing 30 years earlier.

-

Ambient Literature is a two-year collaboration between UWE Bristol, Bath Spa University, the University of Birmingham and development partners Calvium, Ltd. established to investigate the locational and technological future of the book. More info. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.”Full text. ↩

-

Rabelais, François and Douglas H Gordon Collection of French Books (University of Virginia). Le Quart Liure Des Faicts Et Dicts Heroiques Du Bon Pantagruel. A Paris: De l’imprimerie de Michel Fezandat, 1552. ↩

-

All Babbage’s excerpts are taken from the Chapter IX. On the permanent Impression of our Words and Actions on the Globe we inhabit. ↩

-

The leaflet notes contain some very interesting background stories about this recording. ↩

-

Perec, Georges and Marc Lowenthal. An Attempt At Exhausting a Place In Paris. Cambridge, Mass: Wakefield Press, 2010. Find it at the Library. ↩

-

Burgelin, Claude, Maryline Heck, Christelle Reggiani and Georges Perec. Georges Perec. Edited by Claude Burgelin, Maryline Heck and Christelle Reggiani. Paris: Éditions de L’Herne, 2016. ↩

-

A radio adaptation of the Attempt at Exhausting… was produced featuring Perec himself in 1978. An excerpt from this recording is available in the UVA Reveal App. More recently, artist Kyle McDonald, inspired by the Perec’s work, created an art installation and a website crowdsourcing the activity of observation and inscription, of an 8-hour long footage at Piccadilly Circus in London. His tongue-in-cheek message is “click and follow everyone.” ↩