Use the App on UVA grounds

Visit the augmented sites indicated on the UVA Reveal Map. Once at a site, click the “Reveal” button and point your device’s camera at the augmented object. The augmentations should appear on your device.

Use the App on UVA Reveal website

Open the app click the “Reveal” button and point your device’s camera at the trigger image to the left. The augmentations should appear on your device.

History of the Cemetery

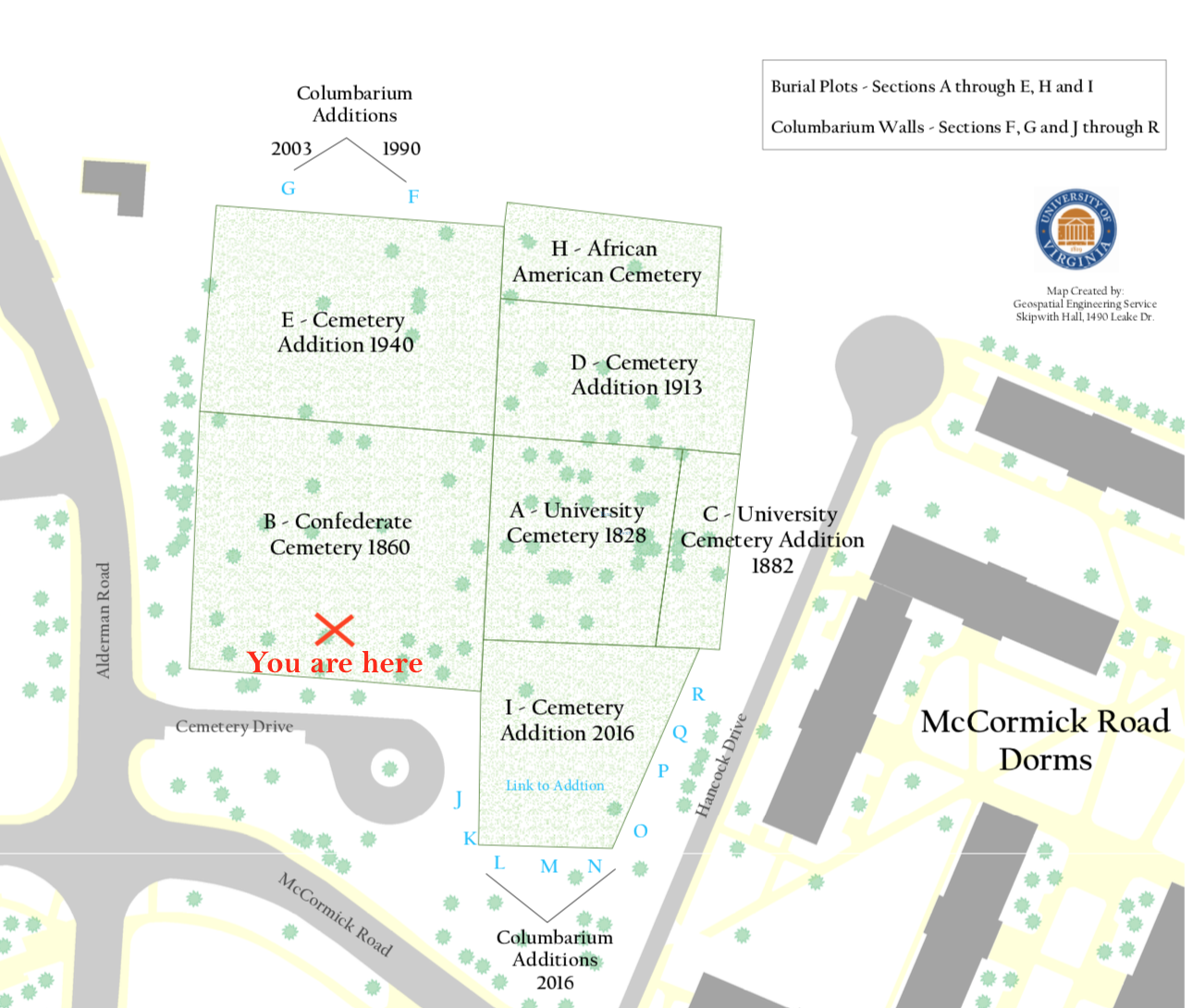

Founded in 1828, the Cemetery at the University of Virginia is the resting place for hundreds of individuals connected with the university, including former university presidents, professors, and students.

During the Civil War, a new portion of the cemetery was created to accommodate the rising number of Confederate dead. This portion of the cemetery –known as the Confederate Cemetery– contains the remains of 1,097 Confederate soldiers, including two Confederate Generals, namely Turner Ashby and Carnot Posey (see more below).

Demand for the Cemetery continued to grow over the years, and the Cemetery was enlarged again in 1882, 1913, and 1940. These additions sustained demand for a while, but by the 1980s, there was renewed interest in expanding the cemetery. In response to this demand, the UVA Board of Visitors “approved establishment of the University Columbarium” in 1987 (UVA Cemetery Committee). Designed by Jack Rinehart, Jr., this Columbarium serves as a memorial wall and “provid[es] 360 vaults in two walls that traverse the northern boundary of the University Cemetery. The two walls were constructed in phases, with completions in 1991 and 2003.”

Given continued demand for cemetery plots, the University Cemetery Committee proposed further cemetery expansion in 2005. This expansion was approved by the UVA Board of Visitors in 2012, and the university began preparing the proposed site, which was just north of the Cemetery. Yet during these preparations, archeological studies “discovered a number of grave shafts believed to be those of enslaved workers and their families” (UVA Cemetery Committee) (see more below). The cemetery expansion was accordingly relocated to the south side of the existing cemetery. The expansion was completed in late 2016, and it “offer[s] the first addition to in-ground burial plots since 1940 and nine additional columbarium walls. In total, the newest addition …provide[s] 263 in-ground plots, including ten presidential plots in a designated area and 544 columbaria niches” (UVA Cemetery Committee). View a video of the University of Virginia Cemetery here.

Confederate Cemetery

As indicated above, the Confederate Cemetery was established during the Civil War to serve as a resting place for Confederate soldiers killed during the war. Because of its proximity to major battle sites (including First and Second Bull Run, Cross Keys, and Cedar Mountain), Charlottesville – and the University of Virginia – became a major hospital area. Over 1,000 wounded soldiers brought to Charlottesville who didn’t survive their injuries were buried in the Confederate Cemetery.

In 1866, after the Civil War had ended, a “group of Charlottesville women, most of whom had cared for sick and wounded soldiers during the war, started the Ladies Confederate Memorial Association” (Maurer). These women recorded the names, states, regiments, and other information of those who had died, and they transferred the information onto “rough wood markers that were placed at the head of each grave. They also collected $1,500, used to build a stone wall around the Confederate Cemetery” (Maurer, “Set in Stone”). By 1890, the Confederate Cemetery was in dismal condition: the wooden headboards had decayed and the cemetery itself was overgrown and unkempt. According to David Maurer, “Distressed by the unsightly condition of the cemetery, the ladies association spearheaded a three-year reclamation effort. The project involved removing rotted grave markers, rerecording names and grave locations and replacing brush and bramble with a lawn of grass. Money for the restoration was raised in various ways, including music concerts and the sale of cream-covered strawberries to students” (“Set in Stone”). June 7, 1893 saw the height of this effort when the statue of a Confederate soldier was erected at the cemetery. This statue still stands today.

The University of Virginia has carefully distanced its own University Cemetery from the Confederate Cemetery; though the two adjoin one another, they are not technically part of the same cemetery. However, when the cemetery was built, the division between the Confederacy and the University was not so stark. 515 of UVA’s 600 enrolled students served in the Confederate Military, and 2,481 of the schools 6,000 living alumni fought for the Confederacy (Jordan).

While only the Confederate dead are honored on the statue, there were Union soldiers from UVA and Charlottesville. 57 students and one professor from UVA served the Union Army during the Civil War. Cavalier Unionists included men like William Meade Fishback, a Virginia native who went on to have a successful political career as Governor of Arkansas. Despite his political prominence and Civil War military career, Fishback’s name was not engraved on the Confederate statue. This omission is part of the University of Virginia’s longer history of ignoring its Union dead in favor of promoting a united, pro-Confederate past (Neumann). In the decades after the Civil War, UVA honored Confederate Cavaliers in numerous ways that expanded beyond the cemetery walls. In addition to rewarding medals to Confederate soldiers and hosting Confederate reunions, the UVA Board of Visitors voted to authorize the Ladies’ Confederate Memorial Association to erect bronze plaques to commemorate UVA’s Confederate dead in 1903. The plaques, which read “The Honor Roll in Memory of the Students and Alumni of the University of Virginia Who Lost Their Lives in the Military Service of the Confederacy 1861-1865,” made no mention of the Unionist UVA alumni. More than 100 years later, The Board of Visitors voted to remove the Confederate plaques from the Rotunda following the violent white supremacist attacks of August 11th and 12th, 2017. UVA students themselves lead the movement to remove the plaques. Read this request and the other demands of the March to Reclaim Our Grounds here.

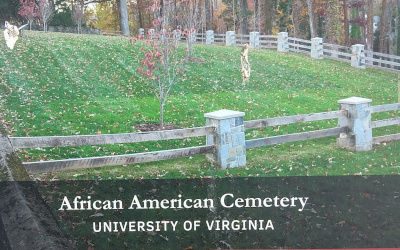

African American Cemetery

In October of 2012, while clearing what seemed to be a plant nursery in order to expand the University Cemetery,archeologists found 67 poorly marked – or wholly unmarked – grave shafts. Benjamin Ford (Grad ‘97, ‘98), the principal investigator of Rivanna Archaeological Services, which oversaw the dig, identified these grave shafts as belonging to former enslaved African Americans. Ford referenced an “1898 Alumni Bulletin, in which the son of a former University librarian referred to ‘servants,’ a common euphemism for ‘slaves,’ in his recollection that ‘in old times, the University servants were buried on the north side of the cemetery, just outside of the wall’” (Qtd. in Wolfe).

The fact that these graves were neglected for over a century is telling. One short wall of stone separates the Confederate Cemetery from these unmarked graves, but the disparity it represents is vast. Across the country, black cemeteries, especially those of enslaved individuals and families, lack adequate and equal preservation and memorialization funds. While the names of Confederate dead are etched into stone in the UVA cemetery, the University did not see fit to record the names of the enslaved men, women, and children buried here anywhere in their records. The smooth grass of the African American cemetery contrasts against the Confederate marble statuary visible across that short stone wall. Slaves often did not get to decide where their family members were buried. Slaves could not install engraved marble gravestones, as they had no wealth to honor their dead. Instead, many slaves in Virginia would select fieldstones to honor their family members. The majority of these fieldstones are not inscribed because slaves were usually denied the time, resources, and literacy in order to inscribe their stones. Despite these barriers, slaves took tremendous care to honor their dead through “settin’ up” rituals, midnight funerals, graveside traditions, and fieldstone or other markers (Rainville). This care has been lost by the University, which did not tend to the slave burial grounds as it did white burial grounds. Indeed, the State of Virginia subsidized this racial disparity by providing funds for Confederate Cemeteries and leaving Africa American burial grounds abandoned. Today, some Virginians are trying to change that. In May 2017, Delegate Delores McQuinn sponsored a bill in the Virginia House of Delegates to provide funds for the preservation of African American cemeteries established before 1900.

The President’s Commission on Slavery at the University of Virginia is also working to preserve this rediscovered African American cemetery. The African American Cemetery has now been turned into a serene pasture and enclosed by a wooden fence. According to Brendan Wolfe, “the newly discovered graves will remain undisturbed and the site will be preserved and memorialized by the University.”

In commemoration of the African American Cemetery, the President’s Commission on Slavery at the University of Virginia commissioned Brenda Marie Osbey to write a poem, which is titled “Field Work.” The dedication of this poem reads: “In Commemoration of the Discovery of the Remains of 67 African Americans, Interred beyond the Walls of the University Cemetery, University of Virginia.” The full text of the poem can be found here. Deborah McDowell gave an interpretive reading of “Field Work” for the Commemorative Ceremony held at the African American Cemetery on October 17, 2014. McDowell’s reading can be viewed here. At this same event, members of a choral group in Charlottesville gathered to perform some Gospel Music over the gravesite. Their performance can be found here.

Sources and Further Reading

- Burns, Jack. “How Restoring Historic Cemeteries Can Shed Light on Forgotten Forefathers.” WTVR. May 17, 2017.

- “Honors at Burial Site.” PCSU Symposium. October 17, 2014.

- Jordan, Ervin L. Jr. “The University of Virginia During the Civil War.” The Encyclopedia of Virginia. March 24, 2016.

- Kapsidelis, Karin. “Turning Point.” UVA Magazine. Winter 2017.

- Maurer, David. “Set in Stone: The Serenity of UVA’s Cemetery Belies a Colorful Past.” Virginia Magazine. Spring 2008.

- Maurer, David. “Yesteryears: UVA’s Confederate Cemetery.” The Daily Progress. May 20, 2012.

- Neumann, Brian. "UVA Unionists (Part 1)." John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History. August 21, 2017.

- Osbey, Brenda Marie. “Field Work.”

- Osbey, Brenda Marie. “Field Work.” Performed by Deborah McDowell on October 17, 2014.

- Parks, Miles. “Confederate Statues Were Built to Further a ‘White Supremacist Future.’” NPR. August 20, 2017.

- Rainville, Lynn. Hidden History: African American Cemeteries in Central Virginia. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014.

- University Cemetery Committee. “History of the University Cemetery and Columbarium.” Cemetery and Columbarium at the University of Virginia. May 2, 2017.

- “The University of Virginia Cemetery.” Video. UVA Magazine. June 29, 2011.

- Wolfe, Brendan. “Unearthing Slavery at the University of Virginia.” Virginia Magazine. Spring 2013.