Use the App on UVA grounds

Visit the augmented sites indicated on the UVA Reveal Map. Once at a site, click the “Reveal” button and point your device’s camera at the augmented object. The augmentations should appear on your device.

Use the App on UVA Reveal website

Open the app click the “Reveal” button and point your device’s camera at the trigger image to the left. The augmentations should appear on your device.

History of the Rotunda

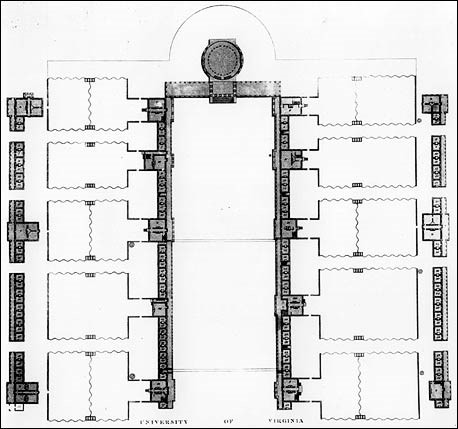

Perhaps the most iconic building at the University of Virginia is the Rotunda, which stands as the centerpiece of Thomas Jefferson’s Academic Village.

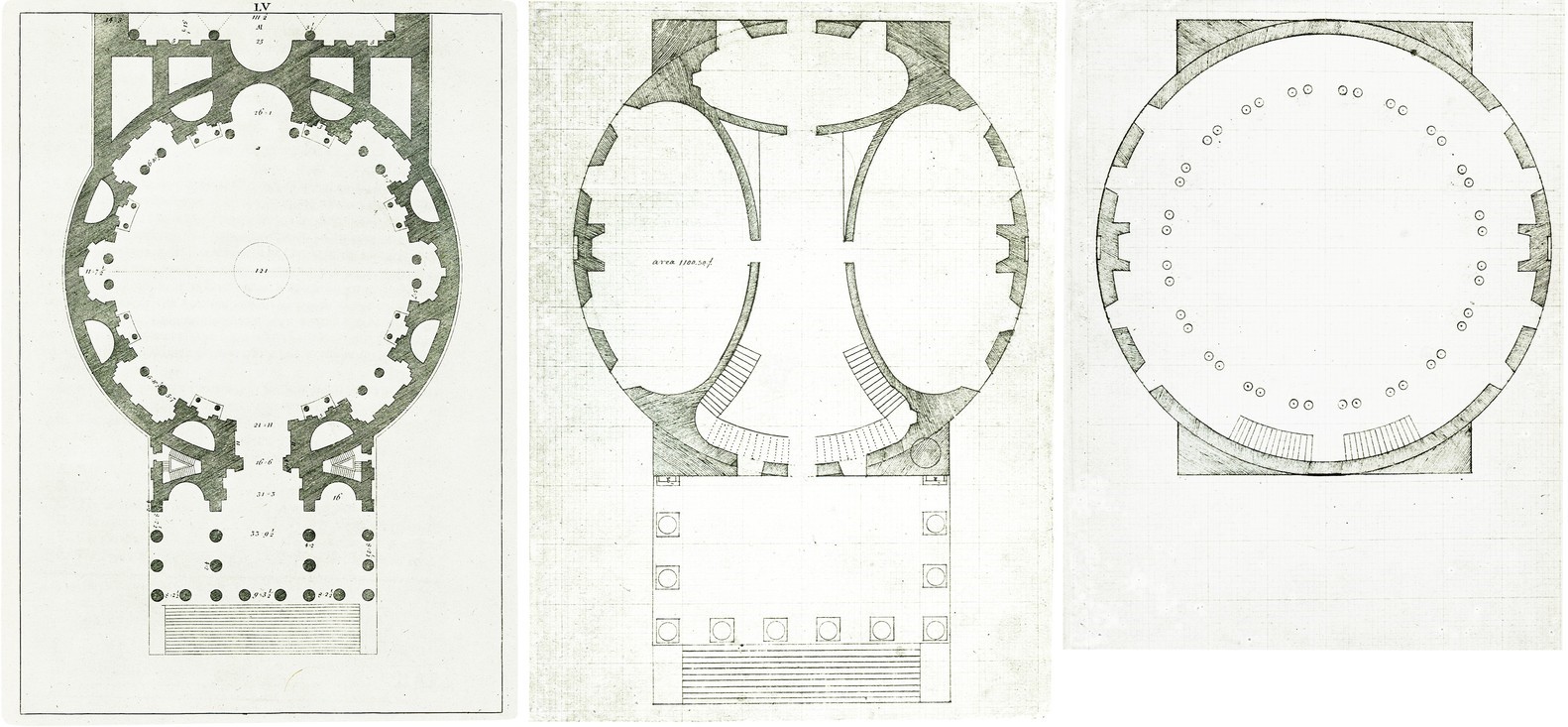

Jefferson designed the Rotunda and proposed his design to the Board of Visitors in 1821. Construction began in 1822 and was completed in 1826, though the steps leading up to the South Portico were not built until 1832. Inspired by classical architecture, Jefferson used the Pantheon in Rome as a model.

On October 27, 1895, the Rotunda caught fire, most likely due to faulty electrical wiring (which was installed in 1888). Unable to subdue the fire, students and faculty rushed to save books and other objects – including the heavy statue of Jefferson inside the Rotunda – from the flames.

In 1896, the Rotunda was redesigned by Stanford White. According to the UVA Rotunda Preservation Committee : “Jefferson had designed the Rotunda with three floors, and Stanford White changed it to two floors, making the Dome Room much bigger. White sought to merge Jefferson’s design with the University’s needs, which still included using the Rotunda largely as a library. He also designed east and west wings on the north side of the building, to match the south wings, and he connected the wings with colonnades. He designed the Rotunda with central heating and a mechanized ventilation system. While the central heat was retained, the ventilation system was scrapped because of cost.” The Rotunda was rededicated in 1898.

The Rotunda has been restored several times since the fire, including in 1976 for the bicentennial celebration. The most recent restoration work began in 2012 and was completed in 2016.

Famous Events and Visitors

The Rotunda has been host to numerous events and countless visitors. Notable among these are Gertrude Stein, Eleanor and Franklin D. Roosevelt, Queen Elizabeth the II, and the Dalai Lama. To see images (primarily from UVA’s Special Collections) showing some of these famous events and visitors, please view the below video:

Hidden Stories at the University of Virginia

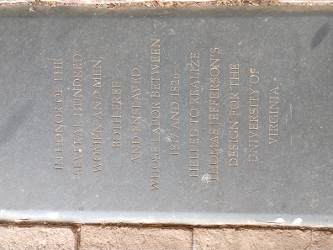

Slavery: Foundations of the University

While it may have been inspired by the ideas of Thomas Jefferson, the University of Virginia was built and run by the labor of enslaved African Americans from 1817 until 1865. According to Brendan Wolfe, “Most of the university’s first enslaved laborers were rented from local landowners and worked alongside whites and free blacks in performing all the tasks associated with building what the school’s founder, Thomas Jefferson, called the Academical Village. In March 1825, the first students arrived and African Americans transitioned to working in the pavilions, hotels, and the Rotunda; maintaining classrooms, laboratories, and the library; ringing the bell; and serving the daily needs of students and faculty.”

Wolfe tells the story of “Anatomical” Lewis and Henry Martin, who both served as bell-ringers of the Rotunda’s Medway Bell. Wolfe writes: “Anatomical Lewis, possibly owned by the university as early as 1830 and as late as 1860, assisted the anatomy professor in what the historian Catherine S. Neale has described as ‘a sordid job and poor living conditions,’ making him ‘an outcast of the community.’ The enslaved man Lewis Commodore had been hired out to the university for a number of years when school officials, learning that his master intended to sell him, purchased him on July 18, 1832, for $580. Commodore rang the Rotunda’s so-called Medway Bell, which marked the day’s schedule, until 1847, when the duty passed to Henry Martin, a free black. Beginning in 1834, Commodore also opened the library each morning and tended to lecture rooms, ensuring they were tidy and warm.”

Most enslaved laborers at the University of Virginia were rented from their owners for a set period of time. Wolfe records that “At the height of building, in 1820, the university paid $1,099.08 in hiring fees. In 1821, hired slaves cost the university $1,133.73, while in 1822 that figure dropped to $866.64, and in 1825, as construction was being completed, it fell to $681. On average, the board of visitors paid owners $60 per slave per year, although the particular amounts depended on enslaved men’s ages, physical conditions, and skills.”

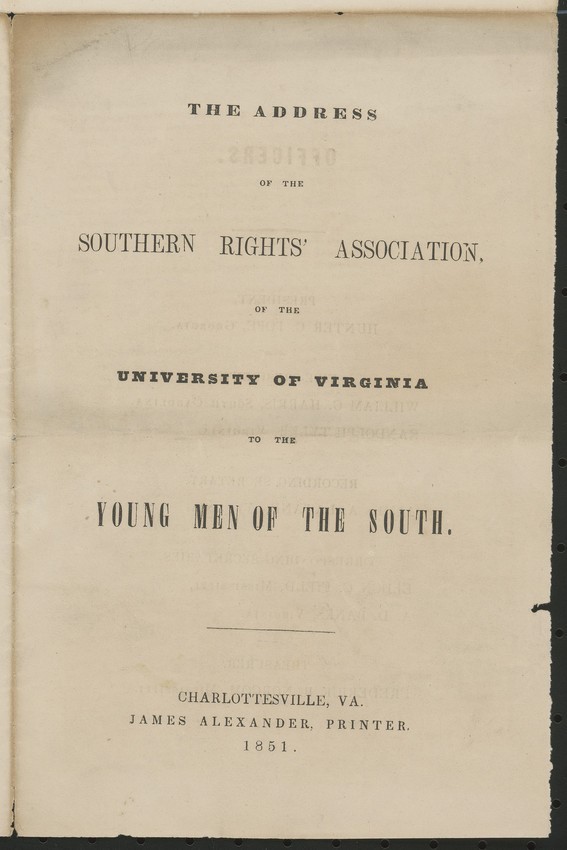

Institutional Racism

Prior to the Civil War, many students and even faculty were outspoken about their support for slavery. In 1850, for instance, students founded the Southern Rights’ Association of the University of Virginia. The Southern Rights’ Association drafted a constitution and published 2,500 copies of a pamphlet titled “The Address of the Southern Rights’ Association of the University of Virginia.” This pamphlet proclaimed the association as “united for the purpose of promoting, as far as we may be able, unity of sentiment and concert of action in the slave holding States against our aggressors.”

Numerous professors also promoted pro-slavery ideology. For instance, Professor Basil L. Gildersleeve, who was a professor of Greek and Hebrew at the University of Virginia from 1856 until 1873, published an essay titled “Miscegenation” in the Richmond Examiner on April 18, 1864. In this essay, Gildersleeve argued for the purity of the “white race” and warned against race mixing. He writes:

“A jealousy natural to our English blood and fostered by our peculiar system, has prevented the intrusion of mongrels [i.e., individuals of mixed race], even of the third and fourth generations, into the society and the privileges of the white race. In no other part of the world, in which the two races [i.e., “white and black races”] have existed, side by side, has this exclusion been so absolute; and it is to this watchful care, which is so natural, that we keep it up unconsciously, and which is so much to our interest that we take no credit to ourselves for it—it is to this watchful care that we owe the supremacy of the white man on the continent, and that we look down so proudly on the mixed population of Mexico and the twenty-two cross-breeds of Lima.”

Current Efforts to Reform

UVA has made efforts to combat its racist history, and in 2013, Dr. Marcus Martin, Vice President and Chief Officer for Diversity and Equity, proposed that a commission be formed to further explore the topic. The result was “The President’s Commission on Slavery and the University”, which includes the creation of a Memorial to Enslaved Laborers (estimated to be completed in Spring 2019) and the establishment of the annual Cornerstone Summer Institute for high school students that “encourages critical thinking while students learn about both the University’s past and the modern-day legacies of slavery.” The Commission has also created a short documentary about slavery at the University.

Founded in 1969, the Black Student Alliance (BSA) at UVA seeks to “represent the social and political concerns of the African-American student body, and to establish a more perfect union between the African-American, multi-cultural, and University communities.” The BSA has been instrumental in implementing changes at the University, and following the August 11th riots, the BSA successfully advocated for the removal of a plaque on the Rotunda that “commemorated members of the University who died serving the Confederacy” (“An In-Depth Look at BSA Demands”). The BSA continues to play a fundamental role in promoting racial equality at the University.

Faculty efforts include a multimedia initiative, Black Fire at UVA, which “document[s] the struggle for social justice and racial equality at the University of Virginia” through photos, videos, and audio interviews. Black Fire is sponsored by UVA’s Office of the Vice Provost of the Arts and organized by Professors Kevin Jerome Everson of the Department of Art and Claudrena N. Harold of the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies and the Corcoran Department of History.

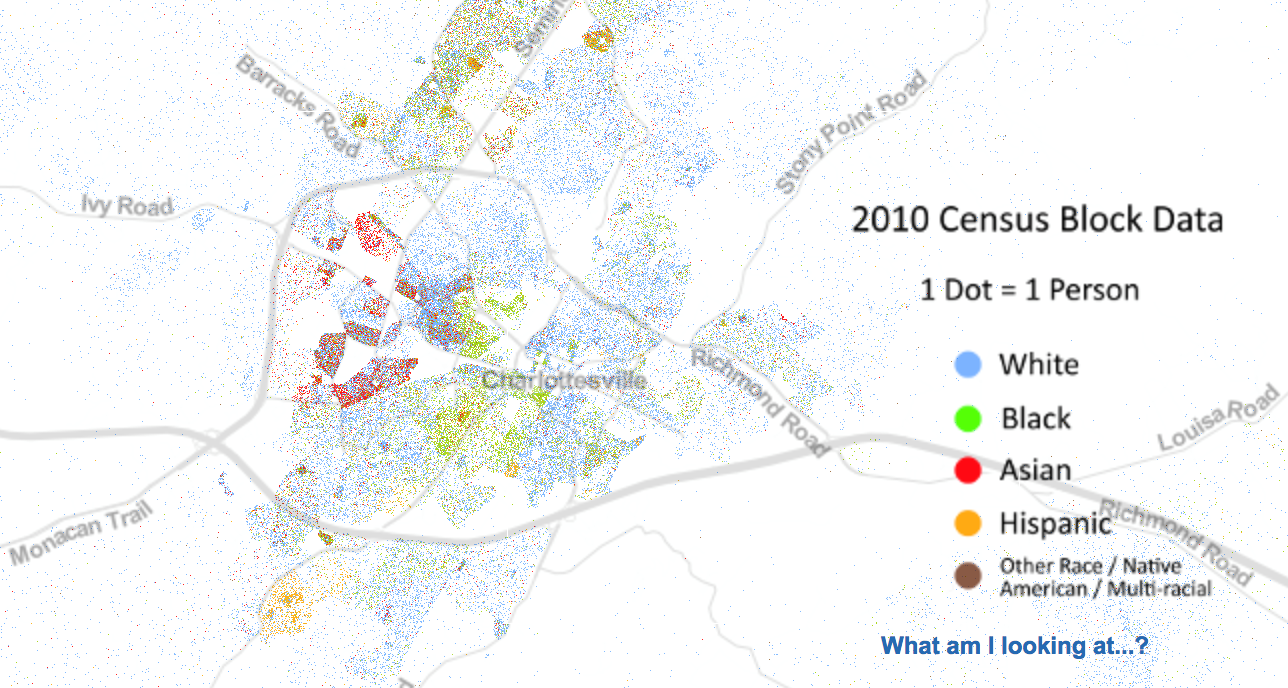

The Demographics Research at the University of Virginia has created a “Racial Dot Map” that visualizes the “geographic distribution, population density, and racial diversity of the American people in every neighborhood in the entire country” using information from the 2010 US Census. This map thus displays how segregation is still endemic to the United States and shows how much more work needs to be done.

Works Consulted and Further Reading

- “The Address of the Southern Rights’ Association, of the University of Virginia, to the Young Men of the South.” Broadside 1851 .V8, Special Collections, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va.

- Black Fire at UVA. Organized by Professors Kevin Jerome Everson and Claudrena N. Harold. Sponsored by UVA’s Office of the Vice Provost of the Arts. 2018.

- Black Student Alliance Movement. 2018.

- Cable, Dustin. “The Racial Dot Map.” Demographics Research Group at the University of Virginia. July 2013.

- Clemmons, Anna Katherine. “Period Pieces: New Book, Exhibits Showcase More of Those Things that Tell UVA’s History.” The University of Virginia Magazine. 2018.

- Gildersleeve, Basil L. “Miscegenation,” Examiner. April 18, 1864.

- Gravely, Alexis, et al. “An In-Depth Look at the BSA Demands.” The Cavalier Daily. August 31, 2017.

- “Meigs Rotunda Plan (1859).” Jefferson’s University.

- Montes-Bradley, Eduardo. “Unearthed & Understood: Slavery an the University of Virginia.” YouTube, Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia. 21 Apr. 2017.

- “President’s Commission on Slavery and the University.” University of Virginia. 2013.

- “The Rotunda at the University of Virginia.” University of Virginia. 2018.

- “The Rotunda: History.” University of Virginia. 2018.

- “Rotunda Reborn: Videos about the Historic Renovation.” Virginia Magazine. Fall 2016.

- Svrluga, Susan. “UVA Acknowledges Its Slave History.” The Washington Post. June 24, 2015.

- “Teaching with Historic Places: Visual Evidence.” National Park Service.

- Wolfe, Brendan. “Slavery at the University of Virginia.” Encyclopedia of Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 2 Feb. 2016.

- Wolfe, Brendan. “Henry Martin (1826–1915).” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 15 May. 2017.